The following article is being reposted here from Los Angeles Magazine:

The following article is being reposted here from Los Angeles Magazine:

The FBI has known about him since his days as a cage-rattling Chicano activist in 1960s L.A. A onetime fugitive and sometime company man, Carlos Montes has kept on confronting the system the only way he knows how. Now the system is closing in

The first raid came at five o’clock in the morning last May 17. Carlos Montes awoke to a thud. It was the sound, he soon discovered, of his front door splintering open. The sun had not yet risen, and Montes’s bedroom was dark, but in retrospect, he says, he’s glad he didn’t reach for a flashlight—or for a gun. Montes, a retired Xerox salesman, had kept a loaded shotgun behind the headboard and a 9mm pistol beneath a pile of towels on a chair beside the bed since the day he had walked in on an armed burglar a year and a half before. That time a cool head had kept him alive: He persuaded the thief to drive him to a 7-Eleven, where he withdrew as much cash as he could from the ATM and refused to take another step. This time, fortunately, he was half-asleep: He stumbled toward the hallway empty-handed.

Montes, 64, is a tall man, but his shoulders are rounded and slightly stooped, which along with his long, thin legs and the short fuzz of his gray hair, gives him something of the appearance of a bird. Maybe it’s that he always seems to be in motion, as if there’s a motor in him that keeps humming even when he’s sitting still. He often seems to be on the verge of cracking a joke, or as if he’s already laughing at the joke he could be telling. Once I showed up early for an interview and found him on the phone, reserving a space in a yoga class. “Gotta take my yoga, man,” he said, laughing at himself, “or else I’ll blow it!”

Standing in the bedroom of his Alhambra home, Montes saw lights dancing toward him. He hadn’t thought to grab his glasses, but when the lights got close enough, he understood that they were flashlights. Green helmets bobbed behind them. Inches beneath each beam he could make out the black barrel of an automatic rifle.

“Who is it?” Montes shouted.

Voices shouted back: “Police!”

Then they were behind him. They shoved him past the ruins of his front door and out onto the patio. Handcuffs clicked around his wrists. It was a cool, misty morning, but Montes could see that his narrow hillside street had been transformed, rendered unfamiliar and almost unreal by the two green armored vehicles parked in front of his house and by sheriff’s black-and-whites blocking the road to the left and right.

A sheriff’s deputy opened the door to one of the patrol cars and pushed Montes into the backseat. He sat there in the relative calm of the police car, the cuffs digging into his wrists, wondering, “What the hell are they going to arrest me for?”

An officer approached the car and told Montes he was under arrest, that he was a convicted felon and it was illegal for him to possess firearms.

“What? ” said Montes. As far as he knew, he’d filed all the required papers for the weapons he owned. The police knew he had them. In 2005, after what Montes calls a “dispute” with a now ex-girlfriend, Alhambra police came to his house and took all his guns “for safekeeping.” (He was arrested on a domestic violence charge, but the case was dismissed.) A year later, after his ex moved out, Montes dropped by the station, and the police returned the guns. “I thought everything was cool,” Montes says.

It was at that point that the morning, already strange, took a stranger turn. Someone from the FBI was there, the deputy told him. An agent in a windbreaker appeared outside the squad car. He leaned in. “I want to talk to you about your political activities,” said the man from the FBI. Montes was not just any retired Xerox salesman. In the late 1960s, he had been one of the most visible and militant leaders of the Chicano movement in L.A. Long after the media spotlight had flickered off, he had continued to agitate and organize against police brutality, inequities in the public schools, and U.S. wars abroad.

Early the next morning Montes stood alone on the sidewalk outside the Twin Towers jail downtown. The sheriff’s department had released him as they had found him: in socks and pajamas, without his cell phone or wallet or change to make a call. Eventually he found a ride to Alhambra. His sister had come by his home and had a sheet of plywood nailed over his front door. But inside, he says, “the house was in shambles.”

Montes was something of a pack rat. He’d saved flyers, clippings, and photos from decades as an organizer of demonstrations and campaigns. “Everything was on the floor,” he says. In his bedroom the contents of his drawers and closet had been dumped out on the bed. Files, albums, and carousels of slides had been removed from his closets and stacked in piles on his kitchen counter and on the dining room and kitchen tables. Political documents were mixed with photo albums from his daughter’s birthdays and his son’s wedding. His guns were gone—the shotgun and the Beretta he’d kept beside the bed plus an old Russian bolt-action rifle, a World War II-era German automatic, and another rifle, a Marlin 30-30. (Montes’s antiwar stance was not grounded in across-the-board pacifism.) His cell phone and computer were gone, too.

Now, months later, Montes stands in his kitchen. His home is tidy but cluttered—the kitchen and dining room tables and every available space covered with neat stacks of papers. Images of Che Guevara, Malcolm X, and Emiliano Zapata figure prominently in the decor. “Once they got the guns,” Montes asks with eyebrows raised, “why did they go through the whole house?”

Forty-odd years earlier an unannounced visit from the FBI, even one fronted by a SWAT team with assault rifles drawn, would not have been surprising. Cold War paranoia had given J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI license to stalk and smear everyone from John Lennon to Martin Luther King Jr. Members of the Black Panther Party were falling by the dozens to police bullets. Through the haze of kitsch that surrounds that era it is difficult to make out the urgency of the times, the until recently almost inconceivable sensation that everything could change and that everyone, even high school kids from the east side of the L.A. River, had a crucial role to play. For a little while East L.A. felt like an important node in a struggle that was being mirrored around the globe—in Oakland, Paris, Mexico City, and Saigon.

But what happened here has for the most part been bleached out of the country’s collective memory of the ’60s. The Chicago Seven made the textbooks, but who remembers the East L.A. Thirteen? Or the Biltmore Six? Those trials have been over for decades, the whole period effectively entombed. And we’ve come a long way, right? The mayor of Los Angeles is a former union organizer and, though he doesn’t like to dwell on it, a onetime Chicano nationalist. The president of the United States is, famously, an ex-community organizer, and both he and his attorney general have much darker skin than Montes. So why is the FBI still interested in Carlos Montes?

In photos taken in the late 1960s, Montes managed to look at once cocky and intensely serious. The character based on him in the 2006 HBO film Walkout—about the 1968 protests at four East L.A. high schools—is portrayed as both joker and firebrand, a militant trickster in a khaki bush jacket. (“Ya estuvo con la blah blah blah,” he says in one scene, shushing his hesitant comrades. “We go out tomorrow!”) A year before the journalist Ruben Salazar was killed by a tear gas canister fired by an L.A. County sheriff’s deputy, he described Montes in the Los Angeles Times as a “lean, intense young man who often sports a Zapata mustache,…noted for his articulateness on the Chicano movement and his wit.”

The son of an immigrant assembly line worker and a nurse’s aide, Montes was born in El Paso and moved with his parents to Los Angeles when he was seven. “I bought into the whole thing about America, the greatest country,” he says. He was majoring in business at East L.A. College when he began to make connections between the Vietnam War, the routine racism of his teachers and school administrators, and the police harassment he and his classmates had faced throughout their teens. With the zeal of a convert, Montes fell in with a group of students who called themselves Young Citizens for Community Action. They opened a coffeehouse named La Piranya just off Whittier Boulevard. It quickly became a social and organizing hub for politically engaged Chicanos, who included future L.A. school board member Vickie Castro, writer and artist Harry Gamboa, and the film producer Moctesuma Esparza. Montes and his peers soon learned an important lesson, one that other young people were learning around the country: You can talk all you want, but the moment you start to organize, the authorities regard you as a threat. Police officers sat in cars outside La Piranya, photographing and hassling people who came and went. More than once the police raided the coffeehouse, claiming they were searching for drugs, frisking everyone inside.

Nothing creates radicals more effectively than repression. The YCCA—by now the Young Chicanos for Community Action—henceforth focused its organizing energies on battling police abuses. In January 1968, says Montes, “somebody went down to the Salvation Army and found a stack of brown berets.” They began wearing them with belted khaki jackets and established a hierarchy modeled on the quasi-military structure of the Black Panthers. Montes, who had just turned 20, was endowed with the grandiose title “Minister of Information.” Salazar referred to him as “the organization’s visionary.”

On March 6 of that year thousands of students walked out of class at Lincoln, Garfield, and Roosevelt high schools, demanding opportunities equal to those taken for granted by Anglo students on the other side of town. Birmingham, Alabama, had arrived in East L.A. The Brown Berets volunteered to form a protective barrier between the students and the police. They found police waiting in the streets and on the football fields. At Garfield, according to one account, snipers were posted on the roof. Montes managed to snap the chain on the gate at Roosevelt. The students who poured past him into the street were met with police batons and fists.

If the newspapers blamed the violence on the students, white L.A. was nonetheless forced to take notice. The Los Angeles Times expanded its vocabulary: “Chichano,” a reporter explained later that year, “is a Spanish expression meaning ‘one of us.’ ” By the end of March FBI headquarters ordered that the Brown Berets be investigated “to determine if activities of the group pose a threat to [sic] internal security of United States.” Within a few months a grand jury indicted 13 of the walkouts’ organizers, including Montes, charging them with a slew of petty misdemeanors rendered serious by the addition of felony charges alleging that the defendants had conspired to commit those same petty misdemeanors. Montes and Ralph Ramírez, the Berets’ “Minister of Discipline,” were in Washington at the time, attending the Martin Luther King-organized Poor People’s Conference. Riots had followed King’s assassination two months earlier, and the D.C. police chief, FBI records show, refused to arrest Montes and Ramírez for fear of inciting more unrest. Instead they were arrested upon their return to L.A.

The East L.A. Thirteen, as they were dubbed, were ultimately acquitted, but 1968 would be a busy year, busier than any until perhaps this last one. The whole world seemed in revolt. Students and workers were fighting police in the streets of Paris—and Chicago. Uprisings were crushed by Soviet tanks in Prague and by snipers’ bullets in Mexico City. Urban guerrilla movements emerged in Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, even Germany. To Montes, the synchronicity was life altering. So was the sense of solidarity, of being part of something larger: a world and a history that stretched far beyond the nest of freeways encoiling the Eastside. “It started becoming clear,” he says, sitting in an Alhambra Starbucks, hunched beneath a straw fedora. “This is not just about police harassment in East L.A. This is a global struggle.”

Brown Beret chapters sprang up around the country. The FBI responded, ordering all offices “having significant numbers of Mexican-Americans in their territories” to gather information on “militant” groups. They began infiltrating the Brown Berets and monitoring them in more than a dozen cities, from Riverside to Miami. Locally Montes’s visibility made him a constant target. Between February 1968 and July 1969, he was arrested seven times. He was convicted only once, of battery on a peace officer—for throwing a soda can at a deputy when police broke up a 1969 demonstration over the lack of a Chicano studies program at East L.A. College—and sentenced to probation.

Montes could not have known that conviction would return to haunt him. He had a more serious case to deal with. In the spring of that year, he and five others—the so-called Biltmore Six—were facing life in prison, accused of lighting fires at the Biltmore Hotel while Governor Ronald Reagan was speaking in the hotel’s ballroom. The police had a witness, a young LAPD officer named Fernando Sumaya who had infiltrated the Brown Berets four months earlier. Moctesuma Esparza was Montes’s codefendant once again. According to Esparza, their lawyer, Oscar Zeta Acosta (who would later gain fame as a novelist and as the model for Hunter S. Thompson’s Dr. Gonzo) learned that Sumaya’s testimony would directly implicate Montes. “Acosta let Carlos know that if he [Montes] was on the case, it would affect everybody. The next thing I knew,” says Esparza, “Carlos was gone.”

Montes likes to talk. His eyebrows leap and fall, punctuating his sentences. His head bobs, and his smile comes and goes. His stories tend to wander, detouring at one aside or another. That laugh of his often breaks out when he arrives at memories that must be painful, as if he’s narrating a slapstick version of someone else’s life. He laughs as he recounts deciding with his girlfriend at the time, Olivia Velasquez, to leave everything and everyone they knew: “Let’s get married, have a big-ass party, and take off.”

They held the wedding in a Boyle Heights backyard, celebrated into the night, and two days later caught a ride to Tijuana. Their plan was to fly from Mexico to Cuba, at the time the destination of choice for American radicals in exile. Except for one friend and Montes’s brother, they told nobody. In February 1970, La Causa, the Brown Berets’ newspaper, reported that Montes had disappeared, speculating that “he may have been kidnapped by the Central Intelligence Agency.” For a little while he was remembered as a martyr. “Carlos Montes will be looked at as a real Chicano Hero,” the article concluded. “In the new history of our people, he lives in the hearts of La Raza, and will never die.”

////

The second raid of this story would come almost precisely 34 years before the first, in May 1977. Montes and Velasquez had made it as far as Mérida, then headed back north to Ciudad Juárez. They had a son there and a year later moved to El Paso, where Velasquez gave birth to their daughter. Over the next five years Montes worked a series of blue-collar jobs under the name Manuel Gomez. He could not resist jumping back into the mix: He got involved in union activism and community organizing, even in electoral politics, though he did his best to dodge cameras and microphones. Montes knew the risks—“We were real paranoid,” he says—and is not particularly self-reflective about his motivations for taking them. He searches for words when I ask him why he took so many chances. “It was something I wanted to do,” he says, and apologizes, “I’m not verbalizing it well. We didn’t discuss whether we should, we discussed howand where.” Activism had become the only way he knew how to live, to situate himself on the planet in a posture that made sense.

In May 1977, Montes and Velasquez risked a trip home to California. Montes hadn’t seen his mother for seven years. His brother had paid him one clandestine visit, but for the most part Montes had been cut off from friends and relatives. The young family spent a weekend with Montes’s sister in Gardena, then dropped in on a family barbecue at Velasquez’s cousin’s house in Monterey Park. “Boom!” says Montes, laughing at the memory. “They raided the house. They had dogs and what looked like M16s.” As police stormed through the front door, Montes bolted for the back. “They rushed in and put a gun in my belly.” Someone had tipped the LAPD.

In Montes’s absence his Biltmore codefendants had been exonerated, but Acosta’s defense strategy had been to blame the fires on Sumaya—and on Montes. (Montes blames them on Sumaya. “I went to the bathroom, and Fernando [Sumaya] followed me,” he recalls. “He pulled a bunch of napkins from the napkin dispenser, threw them in the trash, and just lit them. I said, ‘What the fuck are you doing?’ and I got out of there.”)

After being escorted at gunpoint from his in-laws’ barbecue, Montes spent several weeks in jail trying to raise bail on the Biltmore arson charges that he had fled seven years earlier. “We formed a defense committee, a Free Carlos Montes committee. We did demos, fund-raisers, pickets,” he says. A few months before his trial began, an article appeared in the East L.A. College campus newspaper above a photo of a lanky, bushy-haired Montes wearing shades and pleated slacks. He had spoken on campus about police violence and racial inequities in the schools—“the same topics,” the reporter observed, that “he spoke against back in 1969 as a leader of the Brown Berets.”

But the movement Montes had helped found had begun to crumble while he was still in Mérida. Seven months after Montes went underground, more than 20,000 people marched down Whittier Boulevard to protest the war in Vietnam. The sheriff’s department’s attempts to break up the crowd left three dead—including Ruben Salazar and a 15-year-old Brown Beret—an untold number injured, and Whittier Boulevard in flames. In the aftermath police infiltration and harassment of Chicano activist groups increased exponentially. Rifts opened between the Brown Berets and the National Chicano Moratorium Committee (which had organized the march) as well as within the Berets.

“By 1972,” says Ernesto Chávez, who teaches history at the University of Texas, “it had all fallen apart.” The Berets’ central committee fired the group’s prime minister, David Sánchez, who promptly called a press conference and declared the Brown Berets disbanded. Even the FBI knew it was over: In a classified memorandum filed that February, agents reported that “most [Brown Beret] chapters are either inactive, defunct, or have deteriorated into social clubs.” Surveillance would continue until at least 1976.

Montes had emerged from underground like a revolutionary Rip van Winkle, eager to pick up where he’d left off. The Vietnam War was over, but, as Montes saw it, the old racist system was otherwise in place. His trial was another opportunity to bring attention to the cause, but when he reached out to old friends, he says, “people didn’t want to touch me. I was like a crisis from the past.” Few of his youthful colleagues seemed eager to help. Their youthful militancy had become a liability.

Ten years after the fact, Montes was found not guilty. There was also the matter of the battery-on-a-peace-officer conviction he had picked up in 1969, for which he was on probation when he skipped town, but the judge was convinced that “time has tempered Mr. Montes’s exuberance for radical action,” as he put it, and declined to punish him further for a crime already a decade old. (Thirty years later the judge’s words still spur Montes to giggles.) But even with his legal troubles resolved, Montes says, “No one would hire me.” Eventually an old comrade got him a job at Xerox, as a salesman, and for the next 20 years Montes would spend his weekdays in a suit and tie, hustling copiers in downtown office buildings. “I was kind of the oddball,” he says.

Moctesuma Esparza remembers running into Montes for the first time in decades—fortuitously in the lobby of the Biltmore, where they had last been together as fire alarms went off upstairs. Montes doesn’t recall the encounter, but it was likely less than comfortable. A few years earlier, he says, Esparza had asked Montes not to call him to testify in court. By the time they met, Montes was Xerox’s main salesman downtown. The Biltmore had given him a discount membership to the hotel’s health club. “He seemed to be doing very well,” Esparza says.

Perhaps it was because Montes was spared the disillusion of the bad days of the early ’70s, but he never changed course. In his off-hours he worked on Jesse Jackson’s presidential runs in 1984 and 1988, and on an antipolice brutality campaign following the killing of 19-year-old Arturo “Smokey” Jimenez by sheriff’s deputies in 1991. He tried repeatedly to reawaken the movement. Toward the end of the ’90s, Montes began writing for Fight Back!, a newspaper and Web site affiliated with a small sectarian leftist group called the Freedom Road Socialist Organization. The group—of which Montes says he is not a member—is a minuscule organization, a faction that in 1999 broke away from another group bearing the same name that was itself born of the combination of two other obscure groups with distant origins in the 1969 dissolution of Students for a Democratic Society. It is, in other words, an isolated and tattered remnant of the movement that won the FBI’s attentions a full half-century ago, when it was still referred to as the New Left.

Montes continued to show up at school board meetings to complain about creeping privatization and dirty bathrooms in Eastside schools. He turned out to march against the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan even as the crowds grew smaller with each passing year. He was in front of the LAPD’s Rampart station in 2010, shouting into a bullhorn after police killed a Guatemalan day laborer on 6th Street, and there again in September to commemorate the anniversary of his death.

Montes fell in with the small quixotic tribe that had survived the sucking ’70s with revolutionary faith intact, the tireless picketers most of the city glimpses in passing through raised windows. He didn’t dwell much on the past. His daughter, Felicia, remembers accompanying her parents to constant rallies and community meetings—“That’s been what I’ve known for a long, long time,” she says—but she didn’t learn about her father’s role in the Chicano movement until she was an undergraduate at UC Berkeley, in an ethnic studies class.

I tried a few times to get Montes to talk about how lonely the years after his return must have been, how much disenchantment he must have had to overcome to keep struggling through the era of triumphant Reaganism. His answers rambled; the questions seemed to bounce off him. For him little had changed. None of the wrongs he fought in his youth ever went away—Americans were still killing and dying in faraway wars, young Latinos still contending with police harassment in the streets and with profound inequities in the classroom. The fight was what it always had been. I asked the historian Rodolfo Acuña, who teaches at Cal State Northridge and has known Montes since the 1960s, what he thought kept Montes going. Acuña answered obliquely: “He’s the same today as he was 40 years ago.

Soon, Kelly says, “calls started coming in from friends.” The FBI had raided the Minneapolis office of the Anti-War Committee, the group that had taken the lead in organizing the RNC protests, as well as seven other homes belonging to peace activists in Minnesota, Michigan, and Illinois. Fourteen people had been subpoenaed to testify before a grand jury. All had either been involved in the RNC demonstrations or withFight Back! and Freedom Road.

Montes got a call from Minneapolis. “Be ready,” he was told. The search warrant for the Anti-War Committee office had listed the individuals in whom the FBI was interested: Agents were instructed to search for financial records connected to 22 named “members or affiliates of the FRSO.” Montes was number 14. By the end of 2010, everyone else on the list had been subpoenaed. (They have refused to cooperate with the grand jury.) “I figured, ‘OK, they’re gonna come sooner or later,’ ” says Montes.

It’s easy to blame law enforcement’s renewed scrutiny of political dissent on the September 11 attacks, but activists had begun to feel the chill two years earlier, after demonstrators in Seattle nearly scuttled the World Trade Organization meetings there. In the mass protests that followed in Washington, Philadelphia, and in L.A. during the 2000 Democratic National Convention, federal and local police discovered a new threat or, better put, rediscovered an old one: the homegrown leftist subversive. They responded with tactics that would have felt familiar to veterans of the 1960s—eavesdropping, infiltration, mass arrests, preemptive raids on activist headquarters.

After the World Trade Center towers fell, the FBI’s freedom to engage in domestic surveillance expanded almost without limit. COINTELPRO—J. Edgar Hoover’s counterintelligence program of informants, secret wiretaps, and covert burglaries—was a distant memory, one that few bothered to recall so long as the government’s new targets were foreigners, the 5,000 Middle Eastern noncitizens rounded up for questioning in the months after September 11. But the following year, Attorney General John Ashcroft revised the “Guidelines for Domestic FBI Operations,” redefining the bureau’s central mission as “preventing the commission of terrorist acts against the United States and its people.” The agency was no longer concerned exclusively with solving crimes but with the investigation of potential future criminals. This “proactive investigative authority” made it easier than ever to initiate investigations, demand information, obtain search warrants, and conduct surveillance—both through traditional methods and via electronic eavesdropping on a previously inconceivable scale.

Montes, who had retired from Xerox in 2001, saw the 2008 Republican National Convention as an opportunity to repudiate the political trends of the previous eight years, “to have a big, massive march so the whole world would see that the people condemn Bush.” That June he traveled to Minneapolis to attend a conference of activists who’d gathered to plan the demonstrations. He knew some of them already: Several members of the Twin Cities Anti-War Committee were also members of the FRSO.

Among the new faces was a short-haired woman with a Boston accent; she introduced herself as Karen Sullivan, a lesbian single mother who had joined the Anti-War Committee two months earlier. Montes doesn’t remember talking to her at any length until she initiated a conversation about Colombia at a conference in Chicago. He had long since been divorced from Velasquez and had twice visited the country with a Colombian ex-girlfriend (the one with whom he had fought in 2005). Sullivan told him her girlfriend was Colombian, too. “I said, ‘Oh, they’re beautiful women,’ and she said, ‘Yeah, they got big asses,’ ” Montes says. “I didn’t know if she was trying to bond with me or what.”

In the days leading up to the convention, local police—aided by the FBI and relying heavily on informants posing as activists—raided six homes used by protesters. Dozens were detained at gunpoint. Eight were arrested and charged under Minnesota’s version of the Patriot Act with “conspiracy to riot…in furtherance of terrorism.” (None were convicted. Local police and the FBI later paid out tens of thousands of dollars in settlements to activists.)

The protests were no less eventful. Thousands of demonstrators filled the streets. Montes spoke at the opening rally and, along with many others, was teargassed by police on the last day of the convention. He managed to evade arrest. Among the hundreds who did not was the woman who called herself Karen Sullivan. Montes saw the police take her away. For the next two years Sullivan would remain close with Montes’s friends in Minnesota. She made herself sufficiently useful that her colleagues trusted her with a key to the office and with the group’s bookkeeping. She joined Freedom Road and seemed particularly interested in fellow activists’ travels to Colombia and Palestine.

In the hours that followed the September FBI raids, as activists around the Midwest were frantically calling to check up on one another, Sullivan did not answer her phone. None of the people she had worked with over the previous two years has seen or spoken to her since. The activists deduced that the woman calling herself Karen Sullivan had been an undercover agent, a fact later confirmed by the U.S. Attorney’s office.

What wasn’t obvious was why Sullivan had been assigned to infiltrate the Anti-War Committee, why Obama’s justice department was so concerned with a handful of peace activists or with a group as obscure as the Freedom Road Socialist Organization. The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan may not have been popular, but they also have not provoked anything that could be called a movement. The Occupy Wall Street protests have only focused glancingly on the wars. Despite the rhetoric of Tea Party politicians, socialist revolution in the contemporary United States is about as likely as an attack by the Spanish Armada.

But neither obscurity nor apparent harmlessness have stopped the FBI from testing its new powers. An internal review conducted by the Justice Department’s inspector general in 2010 criticized the bureau for subjecting four antiwar and environmental groups—the Thomas Merton Center, the Catholic Worker, Greenpeace, and People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals—to lengthy domestic terrorism investigations, despite the fact that agents had “little or no basis for suspecting a violation of any criminal statute.” The raids in Minnesota and Illinois came four days after the release of the inspector general’s review.

The FBI and the U.S. Attorney’s office have refused to comment on the investigation—“We can neither confirm nor deny any investigative activity,” says FBI spokesperson Ari Dekofsky—which leaves activists guessing at the government’s motivations. “I think they really believe we’re terrorists,” says Montes with a pained smile. But whatever is behind the searches and subpoenas—whether it’s bureaucratic inertia or a concerted ideological attack—their message is as clear as it was in 1969: Dissent can be dangerous.

The search warrant issued for the raid on the Anti-War Committee office threw a small degree of light on the government’s intentions. Agents were looking for evidence that the subpoenaed activists had violated federal laws prohibiting “material support to designated foreign terrorist organizations”; specifically the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, or PFLP (a leftist faction of the Palestinian Liberation Organization), and the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia, or FARC (one of the few surviving leftist guerrilla forces in Latin America).

In April Kelly and Gawboy made a discovery that clarified things slightly more. Mixed in with their own files in Minneapolis they found papers the FBI had apparently misplaced: the FBI SWAT team’s “Operation Order” for the raid on their home. The documents included a lengthy list of “FRSO Interview Questions,” ranging from the innocuous (“Have you ever heard of the Anti-War Committee?”) to the dramatic (“Have you ever taken steps to overthrow the United States government?”) to the quaintly McCarthyite (“Do you have a ‘red’ name?”) to the absurd (“What did you do with the proceeds from the Revolutionary Lemonade Stand?”).

Many of the questions focused on contact with the FARC and the PFLP. Several of those subpoenaed had traveled to Colombia and Palestine on the kind of odd vacations that earnest activists tend to take: They interviewed organizers and political prisoners, Kelly says, and when they got home, wrote and lectured about their findings. “What we’re talking about is extremely public activity,” says Kelly. “The point of making the trips is to be able to come back and talk about what’s happening.” Montes had visited Colombia twice with his ex-girlfriend. He met labor and human rights organizers there, he says, and a lot of writers—his girlfriend was a poet—but no one from the FARC. He gave presentations on his travels at Pasadena City College and at UCLA. “I had PowerPoint slides,” he says. “I denounced the assassination of labor leaders and indigenous leaders. I tried to get as much publicity as I could.” But the public nature of the trips may be what gets the activists in trouble: In 2001, the Patriot Act broadened the definition of “material support” to include “expert advice or assistance”; another law passed in 2004 expanded it still more to include “service,” a category the Supreme Court has since affirmed may include activities as basic as speech.

When the FBI finally arrived at Montes’s home in May, the agent’s first question would hew to a familiar script. He asked Montes if he would answer questions about the Freedom Road Socialist Organization. Montes remained silent. A sheriff’s department spokesman would later confirm that the raid on Montes’s house had been prompted by the FBI. Montes would be charged with four counts of perjury for neglecting to mention a 42-year-old conviction for assaulting a peace officer—the soda can thrown at police lines during the protest at East L.A. College—on the paperwork he filed when he purchased the weapons, along with one count of possession of a handgun and one count of possession of ammunition by an ex-felon. He is facing a possible prison sentence of 22 years. And like the 23 activists already subpoenaed, he is expecting to be indicted at any time for material support of a terrorist organization.

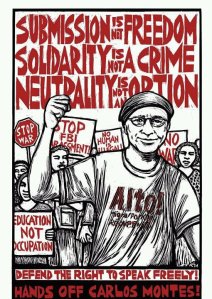

In the months since his arrest there have been fund-raisers in his honor at art galleries and in friends’ living rooms, campaigns to barrage Attorney General Eric Holder with e-mails and letters, and rallies as far away as Philadelphia, Dallas, and Gainesville, Florida. Montes has once again become something of an activist cause célèbre, though that is a humbler role today than it was the last time he was charged.

On September 29, the date of Montes’s preliminary hearing, the sidewalks outside the downtown courthouse are packed with camera crews. Montes paces the sidewalk in a blue pin-striped suit, grinning anxiously and chatting with his supporters, about 40 of whom have come out. A few wear red T-shirts silk-screened with the image of a young beret-clad Montes. They march in tight ellipses, waving picket signs and chanting “Hands Off Carlos Montes!” The reporters ignore them. They are here, it turns out, for the manslaughter trial of Dr. Conrad Murray, Michael Jackson’s physician.

A few LAPD officers stand outside the courthouse, watching idly. Two heavyset women in floral dresses pause beside the picketers, puzzled. Montes hands them flyers. “Oh,” says one woman to the other, “this is something else,” and they hurry on toward the courthouse door.

Someone gives Montes a microphone. He taps it. His voice booms out through a portable amplifier, thanking his fellow activists for showing up. A gaggle of journalists and photographers hustles past. Montes hurries to address them through the mic. “We’re here to support Carlos Montes,” he says, winking, “to keep him out of jail. Take a flyer, take a flyer.” None of them stops. The cars on Temple Street go honking by as they would on any other weekday morning. Reporters settle into folding chairs on the sidewalk across the street. Someone whispers that Janet Jackson has arrived. Holding the mic to his mouth, Montes looks briefly relaxed, almost at home. “I do want to say,” he begins again, “that the struggle continues.”

Ben Ehrenreich’s last piece for Los Angeles, “The End,” won the 2011 National Magazine Award for feature writing. His novel Ether (City Lights Books) came out in October.

ALSO: Read a Q&A with Ben Ehrenreich about this article.